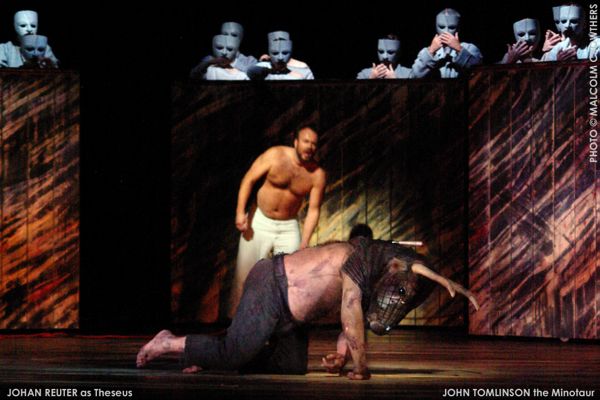

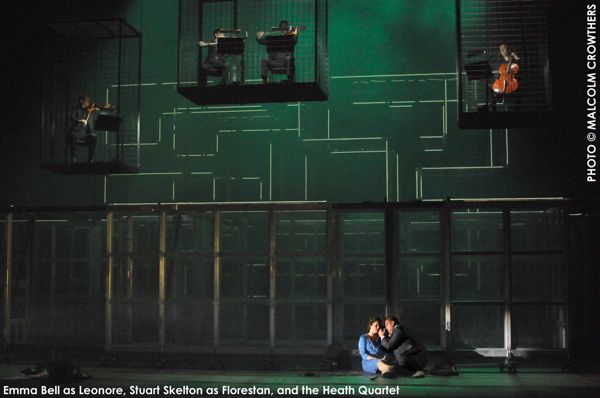

Royal Opera House: BIRTWISTLE’S THE MINOTAUR

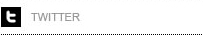

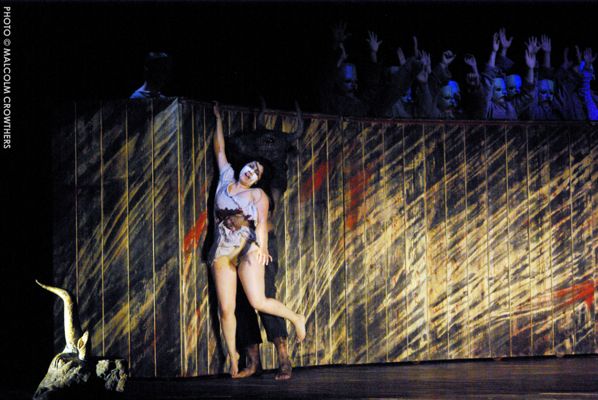

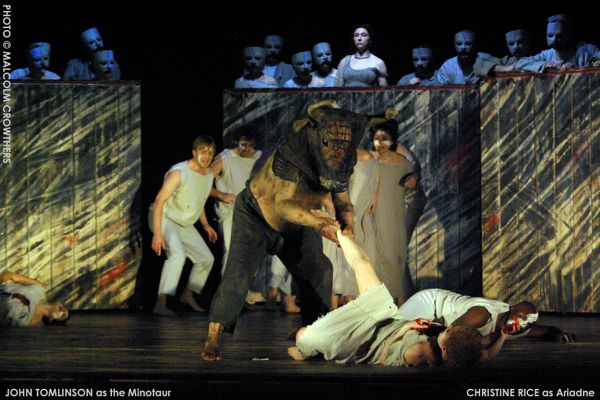

Royal Opera House: BIRTWISTLE’S THE MINOTAURJohn Tomlinson as the Minotaur in Harrison Birtwistle’s opera is mesmerising bringing the half-bull-half-man monster of Greek legend to life, a living legend himself. One of the world’s greatest operatic basses, the First Night of the revival was also his 35th anniversary singing on the Royal Opera House stage. Famous in his innumerable roles as the Commendatore, Boris Godunov, Gurnemanz, Hans Sachs and Wotan, it was his Hagen in Götterdämmerung which inspired Birtwistle to write The Minotaur as a vehicle for his masterly vocal technique and acting skills. After tumultuous applause he was presented with a huge cake and praised most especially for his faultless diction by the Director of Music Antonio Pappano and the way he always brings out the animal in every character! “Whenever I hear that music start I feel frightened” said John as his face, hands and feet were being made up before the performance, because of the journey he’s got to go on. It’s a huge role, physically demanding and vocally challenging in a way no opera singer has ever had to cope with before, as he is the principal character for the whole opera trapped inside a full head and shoulders bull-head mask and hairy body suit. But be amazed, for his diction is phenomenal. When in the Minotaur’s dreams he becomes human and sings as a man, you hear every word as he pours out his inner anguish and it harrows you: “Locked in this body, this pelt this neither-nor, locked in my cage with no key … I’m lost in myself, I look through the eyes of the beast to find the man.” You are made to feel for this monster who becomes almost perversely compelling. Most extraordinary in his bull state are his roars in the bullring at the centre of the Labyrinth as, goaded to the kill by the crowd and the banging of on-stage timpani, he tries to articulate in human speech his name ‘Asterios’ AHHSEOOS (in the score), ‘Man-beast’ AHHHN EHHHSSS, ‘Hunchback … man-freak’ HUUUHBAHH … MAHHH FHREEE, ‘Son of the bull’ SAHHHN AHH EHHH HNUHHLL ‘from the sea’ FRAHHN NEHHH SAAAHHH, (roars) NUUAAAAARGH! No hope after that for the victims, the yearly tribute of Athenian ‘innocent’ boys and girls paid to King Minos in Crete to be sacrificed to the Minotaur in the Labyrinth.There are 3 ritual killing scenes, the first a lone girl gored and raped, the duet of her cries and his roars unique in all opera, then the carnage of lust and murder of the rest, and finally his own killing by Theseus to end the tribute, his death-aria reminiscent of that of Tzar Boris in Boris Godunov, which Birtwistle looked at while composing the opera.

13 images shot by Malcolm Crowthers for FACADES

With the death throes comes a deft surprise touch, a turn for the worse, as the scraping of guiros ingeniously evokes death rattles and announces the coming of the demonic Keres, terrifying harpy like women beating their tattered wings on the ground as with ravenous shrieks and screams of ‘Blood blood’ they claw out with their talons the dripping hearts for a feast of gore. The extreme violence both visually and musically is electric with intensity and horror both in the revival conducted by Birtwistle specialist Ryan Wigglesworth, whose NMC Birtwistle orchestral disc Night’s Black Bird won a 2011 Gramophone Award, and in the superlative 2008 world premiere DVD by Antonio Pappano. Used to conducting Puccini, Wagner and Verdi, Pappano skilfully rachets up the tension to each killing scene, implicit in David Harsent’s terse poetic libretto and Birtwistle’s score, proving the composer a master of pacing both of drama and orchestral colour, and The Minotaur to be a 21st century opera classic deserving performances everywhere.The other principal four cast are exemplary as they were in the 1998 premiere and DVD, with Christine Rice and Johan Reuter returning as Ariadne and Theseus, countertenor Andrew Watts as the bizarrely riveting Snake Priestess with huge bare breasts and tits rocketed up out of the floor to jabber 5 metres high at full throttle, and Alan Oke replacing the late and much lamented Philip Langridge as the priest Hiereus. It is a great night in the theatre. It is grand opera in the grandest sense of the word, very strong, very special, powerfully staged by director Stephen Langridge and designer Alison Chitty. Birtwistle writes from the heart, big structures, beautiful arced melodies. Dark, violent and intense like his early Punch and Judy, it is magnificently melancholy, forcing you to focus on the bestial side of human behaviour. The opening of Dowland’s song “In Darkness Let Me Dwell” subtly pervades the score, like the doom laden clang of the cimbalom. The music falls downwards whenever there is a descent, and in the most haunting of its orchestral Toccatas a twisting winding melody on strings evokes Theseus journeying with the ball of string down through the treacherous Labyrynth to kill the Minotaur. John Tomlinson has an unnerving ability to bring out the pathos and deep anguish of this poor ‘half and half’. Seeing it from the Minotaur’s point of view is a stroke of genius. Like the Minotaur himself, John Tomlinson’s performance could well become legendary and is superbly captured on the ROH Opus Arte DVD, the World Premiere Recording, conducted by Antonio Pappano, a must for all who saw it or missed it.

London Band: Halfpenny Pass

London Band: Halfpenny Passfilmed by JEJ for FACADES

There are always cool new bands sprouting around in old London town, this one caught our attention...

Halfpenny Pass are a North London collective bringing a mix of funk, trip and hip-hop, with guest rappers and singers featuring at both live gigs and on recorded tracks.

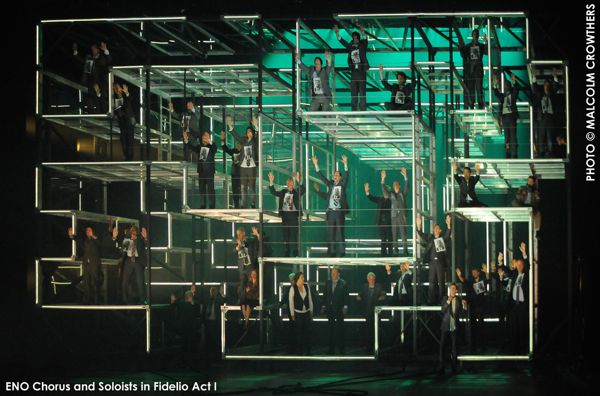

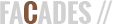

CALIXTO BIEITO’S FIDELIO @ ENO

CALIXTO BIEITO’S FIDELIO @ ENO(11 images shot by M. Crowthers)

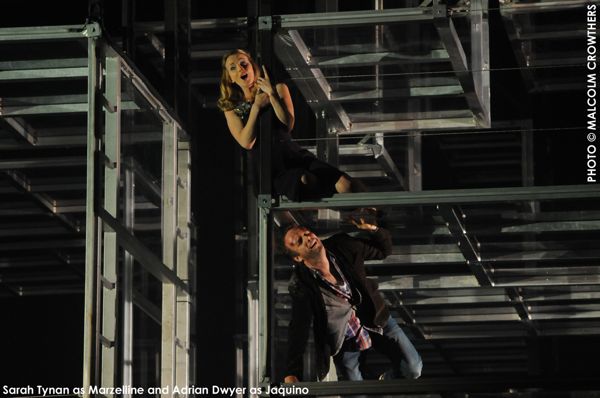

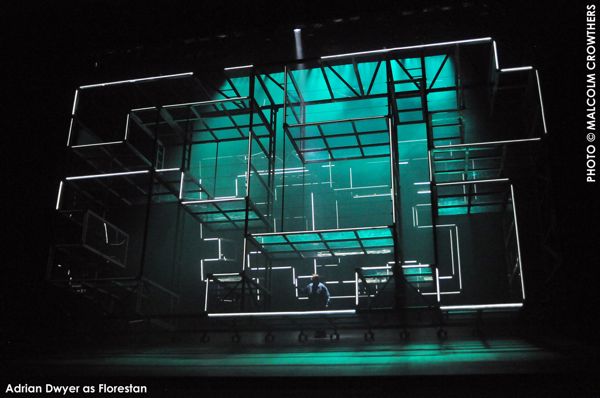

Unmissable, Calixto Bieito’s highly original production of Beethoven’s operatic masterpiece Fidelio at ENO is a remarkable experience. If you like those stylish slightly dark films by Almodovar, the Cohen Brothers and Tarantino, you will engage immediately with this Fidelio. It’s a rescue opera, the story of Leonore, who disguises herself as a man, Fidelio, to rescue her political prisoner husband Florestan from his enemy Don Pizarro’s dank dungeon, snatching him from the very jaws of death back into her arms. Famed Catalan director Bieito takes this traditional story and gives it a very modern edge, visually surprising, arresting and stark. In line with ENO’s theatrical almost cinematic approach to a lot of its productions. Bieito, who stunned ENO audiences last year with his sex cars violence lust love & death Carmen, makes Fidelio a gripping prison drama with an astonishing filmic attention to detail. The stunning set by Rebecca Ringst screams INCARCERATION, a towering steel, glass and flashing neon structure of boxes, ladders and platforms filling the full height and breadth of the London Coliseum’s vast stage, immensely imposing especially filled with the great chorus of prisoners in corporate business suits as if at office block windows, suggesting states of captivity in ourselves, far beyond the distant reality of political prisoners in Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, provoking us to question who we are and how we are all in our own ways prisoners, trapped in the daily patterns of our lives, each in our own box, in our own head. Beethoven knew the terrible solitude of incarceration in his own head caused by deafness. Imagine being a composer of such imagination and not being able to hear a note? Yet such was the condition in which Beethoven led the first performance of the final version of his only opera in 1814 which he had started to write back in 1805, already 4 years after the onset of his deafness at the age of 30. His prison opera was written in the prison of his mind. Reflection is important. The best novels and plays cause us to rethink our lives, and no less should operas and their productions, especially this one by Beethoven the humanist who believed in Liberty and abhorred tyrants, and famously tore up his dedication to Napoleon on his Eroica Symphony when Bonapart declared himself emperor. Beethoven’s message, coined by Rousseau back in 1762, rings loud and clear: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” A director who understands the brutalities of man, Bieito has said he no longer believes that justice still exists as a concept in the world, but what he does believe in is the redeeming power of love. He is one of those great directors who have an intellectual and philosophical approach. There are multiple layers of meaning and deep psychological penetration of every character that makes this Fidelio riveting and rewarding to watch. And what of Beethoven’s music? You could not wish for a better performance. Under the baton of ENO’s Director of Music, Edward Gardner, the orchestra, cast and chorus are all superb.The principal singers prove not only skilful at the finely tuned acting Bieito requires of them but at mastering Beethoven’s often exceedingly difficult vocal lines at the same time, an Olympian feat. At best, as in the First Act Quartet, Emma Bell as Fidelio, James Cresswell as the gaoler Rocco, Sarah Tynan as his daughter Marzelline, and Adrian Dwyer as her lover Jaquino, move us to tears. Equally transfixing is Stuart Skelton as the prisoner Florestan’s searing cry from the soul of the word “God” just after the entire set has turned upside down on top of him to trap him in a labyrinthine cage, a breath taking and chilling sight. Supremely moving again is the masterstroke musically of this production. After the climactic moment that Florestan is rescued by his wife Leonore from being killed by the tyrant Pizarro and reunited with her, unearthly music is heard as if from another world, strange quiet music which Beethoven wrote a decade after his opera as thanks to God from a convalescent recovering from a near fatal illness, the slow movement of his String Quartet Op 132. Gradually it comes into focus as the four players of the Heath String Quartet slowly descend in cages, quite visionary and a true still point before the mighty loud and magnificently achieved finale where the ENO chorus surpass themselves and Roland Wood as the Minister Don Fernando steps suddenly out of the 18th century in full English aristocratic dress to bestow justice, or does he? There is another dark surprise up Bieito’s sleeve to unsettle us, and send us home thinking.